This is old news, but new to Curmie. Grand claims get more press than their refutation does; I missed the latter.

I start this post by acknowledging that the article in the Chronicle of Higher Education upon which it based was written by Ariel Sabar, who’s currently hyping the paperback release of his now four-year-old book on the subject. But it seems well sourced, and if even a substantial minority of his claims are true, then there’s a significant problem here: enough so that the article’s title, “A Scholarly Screw-Up of Biblical Proportions,” seems apt. [Note: the article is likely behind a paywall, so I’ll quote rather more extensively than usual.]

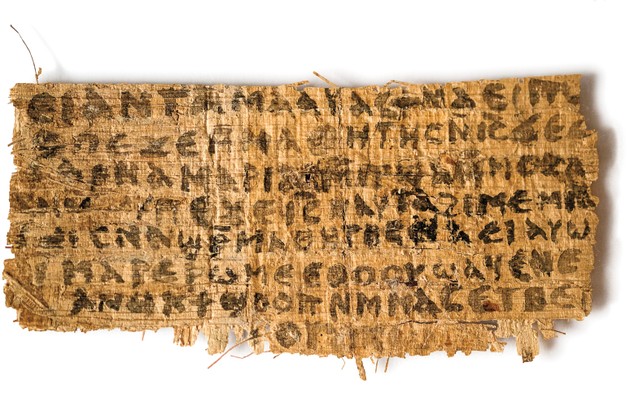

This is not Curmie’s area of expertise, to say the least, but he does remember the headlines from a few years back suggesting that a newly discovered Coptic papyrus fragment had been found in which, to quote that article’s title, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife…’” [This article is also probably behind a paywall; Curmie accessed it through JSTOR.] The article’s author, Karen L. King of the Harvard Divinity School, made quite a name for herself with this alleged discovery. Indeed, those two words were weaponized by those wishing to overthrow/reform/whatever the doctrine excluding women from high positions in the Church hierarchy.

Problem is, it appears to be all bullshit, and even Dr. King pretty much admitted as much in 2016, although neither she nor the Harvard Theological Review, which published her article, seem the slightest bit interested in retracting the essay or even attaching a note of warning to the prospective reader. Let’s face it, the vast majority of readers in 2021 will access the work as Curmie did, online. Retracting the article or attaching a disclaimer would not be terribly difficult, technologically. Indeed, Brill Publishers retracted a similar essay (a chapter in a book) under similar circumstances.

But the problem is that the article should almost certainly never have been published to begin with. And as far as Curmie can tell, literally everyone associated with the publication screwed up: not merely exercising bad professional judgment, but also acting unprofessionally and unethically.

First off, it appears that Dr. King was duped. She’s supposed to be an expert and, well, didn’t live up to the billing. But the wheels don’t really fall off the wagon until this Harvard prof submitted her article to a journal published by her colleagues. Surely everyone knew of her project, and knew that the article in question was written by the holder of the oldest endowed chair in the country.

Here’s where it all goes wrong. Most academic journals work on a “double-blind” vetting system. That is, the author of the paper doesn’t know who is advising the editors on the article’s publishability, and the reviewers don’t know who wrote it. This procedure is designed to make the process as fair as possible: reviewers aren’t advocating for their friends or denigrating their rivals; authors cannot retaliate against negative reviews if they don’t know who wrote them.

So the article is sent out to three authorities in the general field. Two of the three believe the papyrus to be a fake. The third, an “acclaimed papyrologist named Roger Bagnall,” it turns out, had “helped King draft the paper the journal was asking him to review.”

Quoting here from Sabar’s article:

Bagnall warned the journal that he was far too involved in King’s article to peer-review it — and that he was no expert in extracanonical Christian texts. “I wouldn’t want there to be any illusion that I’m in any way an outsider in the way that referees typically are,” he had emailed the editors. But the journal sent his anonymized praise to King as if it had come from a traditional referee. Without Bagnall, the article would have lacked a single positive review. His opinion allowed King to claim that “in the course of the normal external review process” at least one referee had “accepted the [papyrus] fragment.”

OK. So Bagnall pretends to uphold professional standards without actually doing so: the only ethical response is “I cannot be an objective reviewer of this material.” Period. The end. But no, he sings the article’s praises while issuing a caveat, which the journal editors blithely ignore. After the fact, he’s engaging in serious butt-covering (“It’s not the way I would wish to run a journal.”), but he’s a weasel, too. As usual, Curmie intends no offense to actual representatives of the genus Mustela.

Be it noted, too, as Sabar notes in an earlier article, that all this is happening in the wake of the success of The Da Vinci Code (book and movie) and its suggestion that Jesus had married Mary Magdalen, but also after the Vatican had declared the fragment an “inept forgery.” To clarify: King made a major announcement about the scrap of papyrus before submitting her article to the journal; the Vatican (and a host of other sources) registered their disbelief in the fragment’s authenticity in response to that well-orchestrated event.

And there were reasons for those suspicions, including “an odd typographical error that appears in both the Jesus’s-wife fragment and an edition of the Gospel of Thomas that was posted online in 2002, suggesting an easily available source for a modern forger’s cut-and-paste job.”

Leo Depuydt, an Egyptologist at Brown University, declared that “As a forgery, it is bad to the point of being farcical or fobbish. . . . I don’t buy the argument that this is sophisticated. I think it could be done in an afternoon by an undergraduate student.” This quotation, by the way, comes from an article in the Boston Globe headlined “No evidence of modern forgery in ancient text mentioning ‘Jesus’ wife.’” Wait… What???

No one looks good in this, but one supposes the possibility that even a scholar with an international reputation could have been guilty of nothing worse that overzealousness in pursuit of evidence that would buttress her feminist theology. She subsequently claimed that, in Sabar’s words, “she had suspected from the start that the papyrus was forged, but pressed ahead, ignoring red flags, recruiting conflicted scientists, and withholding important facts, photos, and paperwork.”

Any vestigial reputation for integrity she might have had was utterly destroyed by the attempt to authenticate the papyrus: the two scientists enlisted for the effort, neither of whom had specific expertise, were a childhood friend of King’s (who ushered at her wedding) and Bagnall’s brother-in-law. Really.

The whole business gets worse. Sabar, again:

The journal, it turned out, had never peer-reviewed the scientists’ reports — to check, for instance, whether the studies had been properly carried out, meaningful tests of forgery. News media, for their part, were effectively barred from doing their own checks: Harvard Divinity School gave reporters exclusives on King’s article on the condition they contact no scientists or scholars other than those King had cited in her paper.Well, that they not contact other sources before the publication date of the article—not quite the same thing.

Anyway, the most likely scenario is that the fragment was owned, and likely forged, by one Walter Fritz, erstwhile internet pornographer and Stasi Museum director (!). Seriously, if Dan Brown wrote this stuff, he’d be laughed at.

Meanwhile, King asserts that although the fragment is almost certainly a fake, that her article should not carry indication that its conclusions are very much called into question: “I don’t see anything to retract…. I have always thought of scholarship as a conversation. So you put out your best thoughts, and then people … bring in new ideas or evidence. You go on.” Erm… no.

It’s one thing to change your mind about what the appropriate conclusion to be drawn from the available evidence might be. It’s reasonable that new information changes a scholar’s perspective. But to base an entire argument on almost certainly flawed if not outright deceitful materials: this is not to engage in conversation. This is not ignorance of other evidence; this is, plain and simple, duplicitous behavior. “Moving on” can happen only after an acknowledgment of the truth, and such a moment cannot occur without retracting the article or at least putting a marker on it to attest to the likelihood of erroneous information.

Dr. King should demand it; the Harvard Theological Review should do so with or without her blessing.

Don’t hold your breath, Gentle Reader.

No comments:

Post a Comment